A Local Habitation

A Local Habitation One Salt Sea

One Salt Sea Beneath the Sugar Sky

Beneath the Sugar Sky Velveteen vs. The Junior Super Patriots

Velveteen vs. The Junior Super Patriots The Girl in the Green Silk Gown

The Girl in the Green Silk Gown Midnight Blue-Light Special

Midnight Blue-Light Special In an Absent Dream

In an Absent Dream Chaos Choreography

Chaos Choreography Indexing

Indexing Dusk or Dark or Dawn or Day

Dusk or Dark or Dawn or Day Down Among the Sticks and Bones

Down Among the Sticks and Bones The Razor's Edge

The Razor's Edge Midway Relics and Dying Breeds

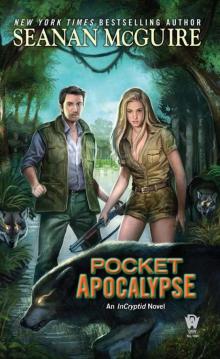

Midway Relics and Dying Breeds Pocket Apocalypse

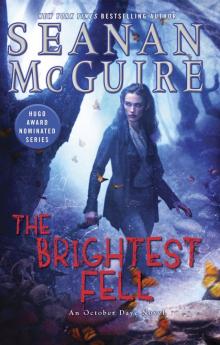

Pocket Apocalypse The Brightest Fell

The Brightest Fell Discount Armageddon

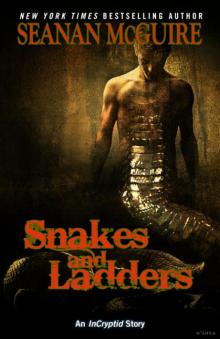

Discount Armageddon Snakes and Ladders

Snakes and Ladders Chimes at Midnight

Chimes at Midnight Broken Paper Hearts

Broken Paper Hearts A Red-Rose Chain

A Red-Rose Chain Married in Green

Married in Green Sparrow Hill Road 2010 By Seanan

Sparrow Hill Road 2010 By Seanan Calculated Risks

Calculated Risks Laughter at the Academy

Laughter at the Academy The Winter Long

The Winter Long We Both Go Down Together

We Both Go Down Together Half-Off Ragnarok

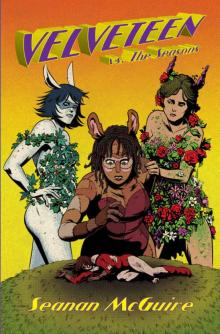

Half-Off Ragnarok Velveteen vs. The Seasons

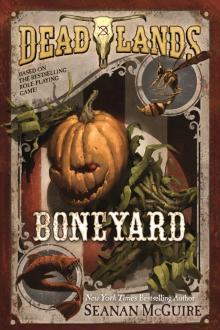

Velveteen vs. The Seasons Boneyard

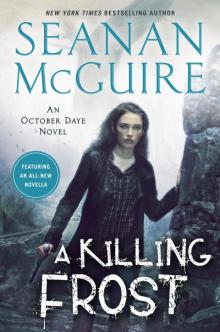

Boneyard A Killing Frost

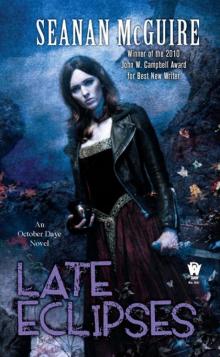

A Killing Frost Late Eclipses

Late Eclipses Submerged

Submerged Blocked

Blocked Velveteen vs. The Multiverse

Velveteen vs. The Multiverse Night and Silence

Night and Silence The Unkindest Tide (October Daye)

The Unkindest Tide (October Daye) Come Tumbling Down (Wayward Children)

Come Tumbling Down (Wayward Children) Snake in the Glass

Snake in the Glass Magic for Nothing

Magic for Nothing Full of Briars

Full of Briars Oh Pretty Bird

Oh Pretty Bird The First Fall

The First Fall Once Broken Faith

Once Broken Faith My Last Name

My Last Name Target Practice

Target Practice Wayward Children 01 - Every Heart a Doorway

Wayward Children 01 - Every Heart a Doorway Sparrow Hill Road

Sparrow Hill Road Middlegame

Middlegame Juice Like Wounds

Juice Like Wounds That Ain't Witchcraft

That Ain't Witchcraft Tricks for Free

Tricks for Free Imaginary Numbers

Imaginary Numbers The Star of New Mexico

The Star of New Mexico Lay of the Land

Lay of the Land One Hell of a Ride

One Hell of a Ride Bury Me in Satin

Bury Me in Satin Heaps of Pearl

Heaps of Pearl Sweet Poison Wine

Sweet Poison Wine When Sorrows Come

When Sorrows Come Every Heart a Doorway

Every Heart a Doorway An Artificial Night - BK 3

An Artificial Night - BK 3 Rosemary and Rue

Rosemary and Rue Black as Blood

Black as Blood Loch and Key

Loch and Key Discount Armageddon: An Incryptid Novel

Discount Armageddon: An Incryptid Novel The Unkindest Tide

The Unkindest Tide Ashes of Honor od-6

Ashes of Honor od-6 A Local Habitation od-2

A Local Habitation od-2 Waking Up in Vegas

Waking Up in Vegas The Ghosts of Bourbon Street

The Ghosts of Bourbon Street Midnight Blue-Light Special i-2

Midnight Blue-Light Special i-2 Bless Your Mechanical Heart

Bless Your Mechanical Heart Chimes at Midnight od-7

Chimes at Midnight od-7 The Way Home

The Way Home Indexing (Kindle Serial)

Indexing (Kindle Serial) Pocket Apocalypse: InCryptid, Book Four

Pocket Apocalypse: InCryptid, Book Four All Hail Our Robot Conquerors!

All Hail Our Robot Conquerors! Were-

Were- That Ain't Witchcraft (InCryptid #8)

That Ain't Witchcraft (InCryptid #8) Night and Silence (October Daye)

Night and Silence (October Daye) Late Eclipses od-4

Late Eclipses od-4 Ashes of Honor: An October Daye Novel

Ashes of Honor: An October Daye Novel Midway Relics and Dying Breeds: A Tor.Com Original

Midway Relics and Dying Breeds: A Tor.Com Original Indexing: Reflections (Kindle Serials) (Indexing Series Book 2)

Indexing: Reflections (Kindle Serials) (Indexing Series Book 2) Chimes at Midnight: An October Daye Novel

Chimes at Midnight: An October Daye Novel One Salt Sea: An October Daye Novel

One Salt Sea: An October Daye Novel Rosemary and Rue od-1

Rosemary and Rue od-1 Rosemary and Rue: An October Daye Novel

Rosemary and Rue: An October Daye Novel Lightspeed Magazine Issue 49

Lightspeed Magazine Issue 49 Alien Artifacts

Alien Artifacts One Salt Sea od-5

One Salt Sea od-5 An Artificial Night od-3

An Artificial Night od-3 Discount Armageddon i-1

Discount Armageddon i-1